BY: JO-EZER LAU

What is Food Fraud?

Food fraud is the deception of customers and final consumers through intentional food (and drink) adulteration. [1] This manner of tampering is manifested by means of substituting one product for another, misrepresenting labelling requirements (e.g. country of origin, malicious contamination with harmful biological or chemical substances), adding unapproved additives, or counterfeiting.

Fraud can be instigated at any point along the supply chain from farm to fork, be it in raw materials, ingredients, the final product, and even in packaging. Monetary gain is the ultimate goal of intentional food fraud, by increasing its apparent value, reducing production costs, and selling the product for a price far higher than its worth.

Food fraud is not exactly a topic that is frequently discussed in consumer circles, for there is a lack of access to and awareness of information regarding food production processes that happen behind closed doors. Furthermore, the effects of food fraud on the human body are not known or readily apparent [2]. According to the Global Food Safety Initiative, ‘most cases of food fraud are not harmful’, and so instances of adulteration predominantly compromise on food quality and not safety. However, past incidents of food fraud that have exploded into nationwide and regional outbreaks have shown that food fraud can pose actual public health concerns responsible for countless lives, especially when the adulteration involved allergens.

Past Incidents

In 1981, a food fraud incident in Spain was closely associated with small scale entrepreneurs and food business operators importing large quantities of rapeseed oil from neighboring countries at extremely low and unregulated prices (Spain only joined the EU in 1986) [3]. These traders sold this cheap rapeseed oil as olive oil, fully aware that the rapeseed oil was industrial-grade (as opposed to food grade) and contained aniline. At the time, public health was deemed to be at stake and investigations continued for years after the incident, but authorities never really established concrete causality on the case, allegedly manipulating data to cover up for failure and shortcomings in determining the root cause. Nevertheless, despite the controversy of the case and whether the fraudulent olive oil directly jeopardized public health [4], the whole motive of selling cheap rapeseed oil as olive oil for monetary gain stands as food fraud, and perhaps this context further sheds light on how far authorities in power can go to prevent the truth behind food fraud from reaching the public.

In 2007, there was a case originating from China where wheat gluten used in pet food was intentionally adulterated with melamine (rather than by oversight), both to add weight and increase the apparent nitrogen value (and thus the perceived protein content) of the pet food. In fact, melamine is a chemical compound found in ceramic dinnerware that is not approved for consumption by the FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius (food standard commission), or by any national food regulatory authority [5].

A year after the wheat gluten contamination incident, melamine was once again found in milk powder exported from China. This time, it was a major food safety incident, with approximately 300,000 reported cases of resulting illnesses and at least 6 infant deaths.

In 2013, the horse meat scandal in the UK shed light on the fraudulent blending of food products with meats from undeclared species [6]. Although it did not cause any major health issues, the incident highlighted the breakdown in the traceability and biosecurity of the food products in a supply chain of complex nature, and the need for stricter preventative control measures in place, both internally and by external food safety authorities.

The incident made many consumers aware, most likely for the first time, of food fraud, and the fact that most products frequently found to be fraudulent are common household food products – for example, the dilution of olive oil with lower quality oils, dried oregano containing ingredients other than actual oregano, or microparticulate cellulose in parmesan cheese, just to name a few. While cellulose may be rightfully added to grated cheese to prevent clumping, some producers have taken advantage of this aspect and added more than needed, with subsequent mislabeling amounting to food fraud.

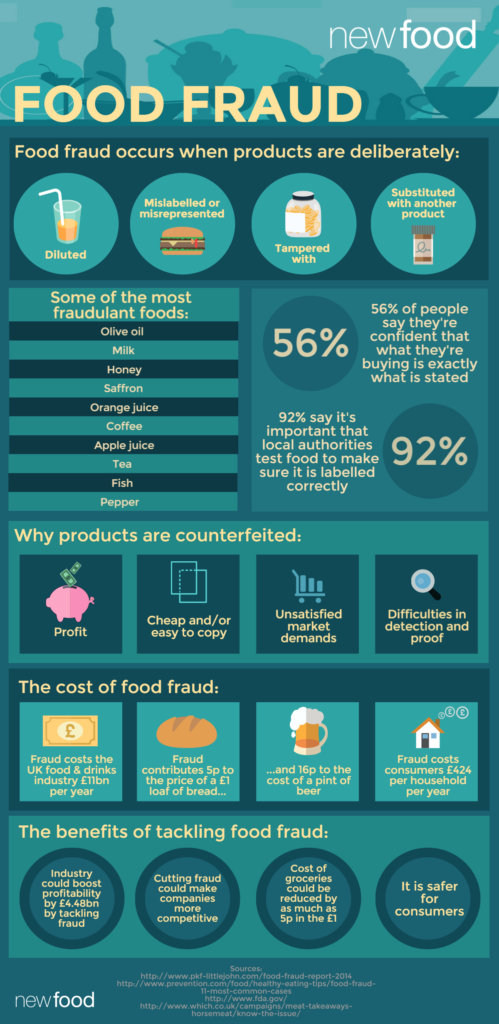

Infographics like this one or by the FDA [7] based on data collected shows that everyday products like milk, honey, tea and coffee are also commonly subjected to food fraud.

Challenges Involved

Food fraud is a crime that is an emerging risk given the complexity of global food supply chains. As per the infographic above, food fraud is costing the industry tens of billions of dollars per year, with households suffering as well from both financial cost and health risks.

Yet, fighting food fraud is extremely difficult because of the nature of adulteration, which often manifests in such a subtle way as seen in the major cases outlined above. Companies go to great lengths to scheme and design the adulterants to be innocuous and almost undetectable by the senses, hence the need for analytical methods. To better comprehend the impact of food fraud and the extent of harm it can cause, we have to broaden our lenses beyond homogenous products e.g. alcohol, olive oil, juices, milk, meat, honey. If this is predominantly the nature of fraudulent food, imagine the extra challenges to detect such adulterations in composite products as well e.g. granola mixes, pre-packaged sushi, ready-to-eat meals, burgers and pizzas etc. It cannot be negated that potential food fraud to this extent is possible, considering the modern changes in food habits i.e. increased consumer demand for convenience food which requires essentially little cooking before consumption).

Role of Regulatory Authorities

At a national level, regulatory bodies such as the US Food and Drug Administration, UK Food Standards Agency, and the Food Safety Authority of Ireland have increased research and development in this area and established control systems to combat food fraud.

In the EU, for example, there is the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) [8]. This tool enhances the traceability frameworks in place by speeding up the flow of information to suppliers, customers, and food regulatory authorities when public health risks are detected in the food chain enabling counter measures to be executed quickly and contain the damage. While this may not always be caused directly by food fraud, at least any arising food safety risks revolving around food fraud would be subject to an efficient handling mechanism.

The EU Food Fraud Network was also established as a response to the Horse Meat crisis to help strengthen their approach to food safety and keep it to the highest standards in addition to the existing standards e.g. ISO 22000:2018 – Food Safety Management Systems which also address food defense and food fraud.

Experts suggest the best way to prevent adulteration within an organization is for employees to expose wrong-doing to the appropriate channels. NSF International, a Michigan-based product testing, inspection and certification organization, recommends encouraging whistle–blowing by company employees based on a COSO study indicating that ‘a tip’ was the most successful source of initially detecting occupational fraud [9].

Generally, companies can prevent food fraud by [10]:

(i) Improving supplier relationships.

(ii)Establishing effective auditing strategies including anti-fraud, malicious activity and espionage measures.

(iii) Ensuring suppliers of raw materials and packaging are certified or not third-party audited.

(iv) Encouraging whistle-blowing.

(v) Collaboration and information sharing between public and private interests.

AND MOST IMPORTANTLY

(vi) Investing in and exploring real-time analysis and new technologies to fight food fraud!

The fact that established organizations, with all the sophisticated processes in place and quality assurance checks at their fingertips, can stoop so low as to reap economic gain at the expense of health and safety through manipulating our basic needs reflects how we have perhaps forgotten how to be human amidst all our progress. While it is somewhat ironic that vast fields of research exist because of a problem that humankind created for itself, consumers can take comfort in the fact that the advancement of science and analytical methods only make food fraud more difficult, and the former, hopefully, will eventually stifle the latter.

The onus for food quality is now firmly placed on the food manufacturers and sample testing is a key part of every food preparation protocol. Consequently, there is great demand from the food industry for effective and affordable means for the routine testing of their products.

The following posts in this series will explore how consumers can play a part in fighting food fraud, analytical methods that have emerged in recent times, employed by the food industry to crack down on traceability and fight food fraud.

Stay tuned in and watch this space for our next post on exploring wine fraud with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) fingerprinting!

(P.S. Come check out our Instagram and Facebook for more weekly IFTSA updates, news, and food science!)

References

[1],[2] Smith, G.C., PhD. (2016). What is Food Fraud?, Available at http://fsns.com/news/what-is-food-fraud, [online]. Accessed 30 May 2019.

[3],[4] Woffinden, B. (2001). Cover-up – Twenty years ago, 1,000 people died in an epidemic that spread across Spain. Poisoned cooking oil was blamed – an explanation that suited government and giant chemical corporations. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2001/aug/25/research.highereducation [online]. Accessed 1 June 2019.

[5] Sharma, K., & Paradakar, M. (2010). The melamine adulteration scandal. Food Security, 2(1), 97–107

[6] Premanandh, J. (2013). Horse meat scandal – A wake-up call for regulatory authorities. Food Control, 34(2), 568–569.

[7] White, V. (2017). Food Fraud: a challenge for the food and drink industry. Available at https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/article/22854/food-fraud-an-emerging-risk-for-the-food-and-drink-industry/, [online]. Accessed 1 June 2019.

[8],[10] Lyons, J. (2018). The rise of food fraud and its impact on food safety. Available at: https://www.rentokil.com/blog/food-fraud-food-safety/#.XP43XIgzbIV [online]. Accessed 31 May 2019.

[9] Smith, G.C., PhD. (2016). What is Food Fraud? Available at http://fsns.com/news/what-is-food-fraud, [online]. Accessed 30 May 2019.

Great post! A topic well worth addressing.