BY: PAT POLOWSKY

It’s often easiest to think of the food industry as being made of two parts: food producers and food sellers. Although this is a simple mental split to make, it doesn’t even begin to capture the true complexity that makes up our food production and retailing ecosystem.

Food Industry Landscape

Let’s draw a rough mental picture of how the food industry is structured. Starting at the top, we have customers and consumers. These are the folks who buy and use food products, respectively. The classic example is the parent – child dynamic. A parent buying baby food is the customer, and their child is the consumer. They can purchase food from two main places: retail establishments (like grocery stores) and food service operations (like restaurants). These places now act as customers and purchase food products from deeper within the supply chain.

Where do they source their products from? It gets a little more complicated from here.

The simple case, and what we often think about, is when a food producer or consumer packaged goods (CPG) company sells a nationally branded product to a retailer. And this situation certainly happens quite often. However, many times there are one or more intermediaries between the producer and retailer who makes the food and who sells the food. There is a diverse world of brokers, distributors, and importers that assist smaller food companies with logistics and business development and will sell products into retailers on behalf of the manufacturer.

Anyone who has worked in the food service or restaurant world will be very familiar with distributors like Sysco or US Foods.

Another flavor of this kind of relationship is how private label goods make their way to the shelf, of which I have first-hand experience. Private label products are also known as “store brands” or “generic” goods. They have gained traction the last few years due, in part, to eroding brand loyalty. While national brand icons get notoriety and air time, private label food product sales can easily have over 25% sales penetration for some grocers. It can be close to 100% for retailers like Aldi and Lidl, who specialize in private label products and forgo most national brands. In these cases, food manufacturers (some of which also make the branded item) will sell food into retail establishments, but often at lower cost since there isn’t the normal marketing overhead associated with it.

The path of a food product from “farm to fork” is rarely a straight line. The logistical network in place to ensure a constant food supply is amazing when you think about it. Image © Pat Polowsky.

We can now turn our attention to copackers and co-manufacturers. These businesses will often produce, process, package, and assemble food items on behalf of another company. In fact, there are some big-name food companies in the marketplace that sell iconic brands, who don’t produce those foods themselves. They rely on a copacker to make the food item, but will market and resell the item under their label. Also, a possibility is that a manufacturer who specializes in private label goods will serve as a “back-up” and produce nationally branded items when demand gets high or interruptions in supply occur.

I’ve personally seen this play out with peanut butter, where a large national player will use a private label co-manufacturer when they need extra help fulfilling larger order volumes from retail chains.

Further down the food supply chain we have ingredient suppliers and the agricultural commodities themselves. Just as complex as traditional food manufacturers, there are a variety of companies who specialize in producing certain food inputs. In this case, food manufacturers are the customers who purchase these ingredients and then produce a shelf-ready food product. Examples of ingredient companies could be flavor houses (who specialize in creating flavors, seasonings, and other tasty ingredients), starch/gum suppliers, enzyme producers, etc.

The degree of vertical integration can vary greatly depending on the specific company and/or sub-specialty in the industry. For example, a sausage company could own hog farms, produce sausage casings, grind pork, have an internal flavor house, and produce a nationally branded sausage item (this would be an example of a company that is very vertically integrated). On the other hand, there are companies that do nothing other than market and sell the item.

For example, an egg hatchery could be a separate entity from an egg packing facility, and furthermore the egg company that sells into retail can be an independent company as well.

To see another example of this, read on!

An example of an egg packing line. This company buys eggs from a hatchery, then washes and packs them.

An example of an egg packing line. This company buys eggs from a hatchery, then washes and packs them. Image © Pat Polowsky.

What goes into a slice of cheese?

To tie all this together, let’s go through an example scenario (which may or may not be based in reality). We will discuss a package of sliced cheddar cheese sold by a national brand. For simplicity sake, let’s call this company Majora®. We’ll work our way through the supply chain and see how it gets to the shelf!

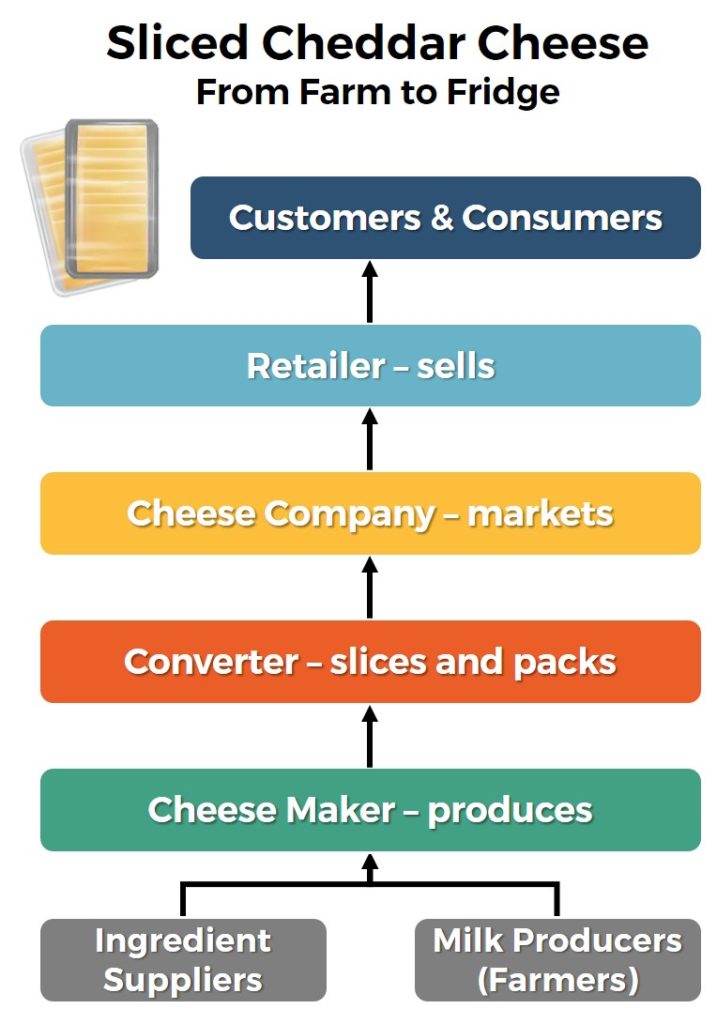

An example of a cheese product’s supply chain.

An example of a cheese product’s supply chain. Image © Pat Polowsky.

The ingredient declaration for cheddar cheese is milk, cheese cultures, salt, enzymes, and color:

- Milk is produced by dairy farmers. It can get even more complicated if you consider situations like and the like. (A dairy co-op, or cooperative, is a collection of dairy farmers who pool their milk to make dairy products)

- Cheese cultures and similar ingredients are produced by firms known as “culture houses”. They grow cultures/bacteria used for cheesemaking. They can also produce the colorants and enzymes used in cheesemaking.

- And finally, we need salt, which would be sourced from an ingredient supplier.

- Alternatively, all of these could also be sourced from a broker/distributor if the cheese company was too small to hit the order minimums set forth by the culture house/ingredient suppliers.

Now to the actual cheese making! A cheese company would source the ingredients above, and then produce cheese. This cheese can end up in a multitude of places, but for our purposes we are going to consider the scenario I described above. This cheese producer has worked out a detailed specification with Majora® of what this cheddar cheese needs to be. Cheese is produced to this spec and is being made in large 640lb blocks (known as 640s in industry parlance).

Guess what the next step is: it’s shipped to Majora®?

Nope, guess again…

Filling a form for a cheddar 640.

Filling a form for a cheddar 640. Image © Pat Polowsky.

These 640lb blocks are then shipped to a converter. A “converter” is cheese industry jargon for a company that cuts, slices, sheds, and/or packages cheese. These firms don’t technically make cheese – they just specialize in getting it into a retail-ready format.

The majority of the cheese that is sold into supermarkets gets there by way of a converter.

This is especially true for private label cheese, which dominates this category for most retailers. In our case, the converter cuts the 640lb blocks down successively and ultimately ends up with 1lb “shingle packs” of cheddar cheese packaged in Majora® branding. Our company, Majora®, then receives and warehouses this product and ships/sells it into retail establishments where customers can then purchase it.

Something to think about the next time you put a slice of cheese on your sandwich!

Pat Polowsky | Linkedin | Website

Pat is a Ph.D. student in Agricultural Education & Communication at Purdue University. Most recently he was a senior product development manager on Walmart’s Private Brand team supporting the deli, entertaining, and gourmet categories. Previously he’s worked in Vermont and Wisconsin, focusing on cheese R&D, sensory science, and software development. In his free time, he runs cheesescience.org, an online educational toolbox for all things cheese. His passion in life is communicating food science in a visual and engaging way. Some folks like gardening on the weekend, whereas Pat enjoys making PowerPoint animations of casein micelles. He has his B.S. in Food Science from Purdue University and his M.S. in Food Science from the University of Vermont.

Leave a Reply