BY: ABBIE SOMMER

Doing research on soy functional foods has led me to become accustomed to that delicious beany flavor of soy ingredients. As I munch on soy pretzels, I find myself thinking about how soy has been portrayed in the media recently. I’m increasingly finding more food products with the label “Soy Free” and more blog posts citing soy as a problem. However, this is not the only soy claim that appears on product packaging.

The CFR states that soy protein may reduce your risk of coronary heart disease1 . In 1999 the Food and Drug Administration approved this health claim for use on food product labeling. This is a big deal because the FDA only approves a small number of health claims that suggest a link between a food or supplement and the risk of disease. In fact, there are only 12 health claims currently approved by the FDA2. Some of them seem obvious, like the positive link between calcium and Vitamin D in prevention of osteoporosis and that between sodium intake and hypertension. These claims must be supported by scientific evidence and agreement among experts2. The soy claim has an extensive history dating back almost 80 years.

One of the first studies about soy protein and health was published in 1941, where researchers fed rabbits copious amounts of soy protein and as a result they found a reduced risk of heart disease3. Of course this was only a small study done in animals, but since then, there have been multiple studies in humans that agreed with this finding4. While the true reason behind the reduced risk of LDL cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol) and, therefore, heart disease, is not yet understood, many researchers have explored the idea that protein, fiber, or phytochemicals known as isoflavones may be the key5.

On the other hand, you may have heard that the FDA proposed to revoke the health claim of soy reducing risk of cardiovascular disease. In 2017, the FDA released a statement saying that current evidence no longer supports the claim6. A final rule has not been issued but studies have followed up on this statement.

The FDA reviewed 46 specific studies to help make a decision on the health claim4. However, the FDA did not perform a meta-analysis, which combines data from multiple studies and analyzes it together. A recent external meta-analysis published this year reviewed those studies that the FDA was considering when the notion of repealing the health claim came about. It found that eating soy protein reduces LDL cholesterol by about 3%, the notion that lead to the initial health claim4.

This reduction in cholesterol is smaller than that initially reported in 1999, but it was highly significant4. In addition to the modest reduction in the risk of heart disease, soy and its components may have other health benefits. There is strong evidence that soy phytochemicals improve hot flashes and arterial health in post-menopausal women and preliminary evidence for reduction of breast and prostate cancer7.

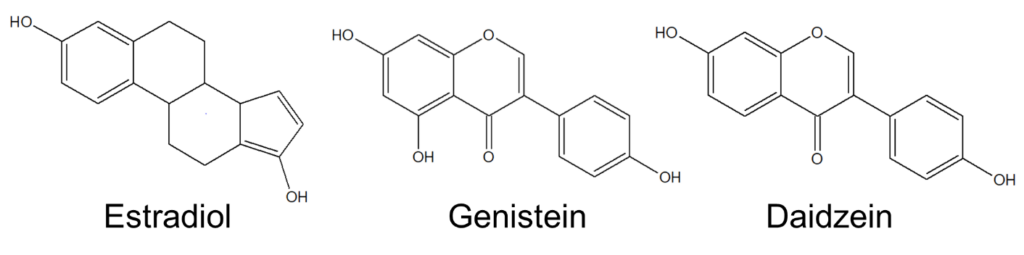

Soy, what’s the problem? Recently, soy has been criminalized in the media with claims of it causing breast cancer, thyroid problems and dementia8. There have also been theories that soy will cause decreases in testosterone or increase feminization9. The shift in attitude stems from the phytochemicals previously mentioned, isoflavones. Isoflavones including genistein and daidzein have a specific structure that resembles estrogen. For this reason, they can bind to estrogen receptors in the body8.

However, binding to estrogen receptors does not necessarily mean there will be a negative health outcome. Think of the isoflavone as a key and estrogen receptors as a lock. The isoflavone key may fit the lock, but not as well as estrogen. This leads to relatively weak estrogen-like activity which could even be beneficial for hormone-dependent conditions such as cancer and menopausal symptoms10. Meta-analysis has shown that soy does not increase breast cancer risk but instead may slightly reduce this risk11. There was also shown to be no changes in thyroid hormones and a slight increase in thyroid stimulating hormone12. Research also shows that soy and its component isoflavones do not have an effect on testosterone in men13.

Photo by Valeria Boltneva from Pexels

So, what does this mean for you? Keep on eating your tofu, edamame, and vegan protein shakes. At least for now, there does not appear to be a negative health effect from eating soy. Soy is a good source of high-quality protein, fiber, and B vitamins8. To get more soy in your diet, try adding in tofu, edamame, soy cheese, plant-based burgers, tempeh, miso, or just plain soymilk.

References

- Food and Drug Administration, HHS. Food Labeling: Health Claims; Soy Protein and Coronary Heart Disease. Vol 21 C.F.R.; 1999:57700-57733.

- Food and Drug Administration. Authorized Health Claims That Meet the Significant Scientific Agreement (SSA) Standard.

- Meeker DR, Kesten HD. Effect of high protein diets on experimental atherosclerosis of rabbits. 1941;31:147-162.

- Mejia SB, Messina M, Li SS, et al. A Meta-Analysis of 46 Studies Identified by the FDA Demonstrates that Soy Protein Decreases Circulating LDL and Total Cholesterol Concentrations in Adults. J Nutr. 2019;149(6):968-981.

- Potter SM. Soy Protein and Cardiovascular Disease: The Impact of Bioactive Components in Soy. Nutr Rev. 1998;56(8):231-235.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Food Labeling: Health Claims; Soy Protein and Coronary Heart Disease. Vol 82.; 2017:50324-50346.

- Messina M. Soy and Health Update : Evaluation of the Clinical and Epidemiologic Literature. Nutrients. 2016;8(12). doi:10.3390/nu8120754

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Straight Talk About Soy. The Nutrition Source.

- Kadney M. Is Soy Bad For You? Runner’s World.

- Vitale DC, Piazza C, Melilli B, Drago F, Salomone S. Isoflavones: estrogenic activity, biological effect and bioavailability. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;38(1):15-25. doi:10.1007/s13318-012-0112-y

- Trock BJ, Hilakivi-clarke L, Clarke R. Meta-Analysis of Soy Intake and Breast Cancer Risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(7):459-471. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj102

- Otun J, Sahebkar A, Östlundh L, Atkin SL. Systematic Review and Meta- analysis on the Effect of Soy on Thyroid Function. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1-9. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40647-x

- Hooper L, Ryder JJ, Kurzer MS, et al. Effects of soy protein and isoflavones on circulating hormone concentrations in pre- and post-menopausal women : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(4):423-440. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp010

Abbie Sommer | Linkedin | Website

After graduating with a B.S. in Food Science from Purdue University, Abbie decided to move one state over to pursue a Masters from Ohio State. Her research is focused on soy-based functional foods for use in clinical trials. When she’s not making thousands of soft pretzels (for science, of course), you can find her training for half marathons or experimenting in the kitchen. Recently, Abbie has developed a passion for sourdough and treats her starter like a child. She also has a recipe blog (Sommer Eats) as well as an Instagram account (sommer_eats), where she posts somewhat healthy but always delicious recipes.

Leave a Reply