BY: ALEX PIERCE-FELDMEYER

As a child on Saturday mornings I often awoke to the smell of bacon and pancakes on a griddle. The second level of my house was rich with breakfast aromas and suggested that something delicious might be waiting for me downstairs if I could just get myself out of bed. This is one of my favorite childhood memories and to this day it comes back every time I smell any sort of prepared hot breakfast. It can be dining out for brunch or scrambled eggs for dinner, but every time that familiar emotion and memory from my youth comes flowing back with that smell. But imagine if one day that all disappeared—the smell, the emotions, the memory.

Poof. All of it.

I just wake up and my sense of smell is suddenly lost.

Gone. Finito.

Not only do I no longer have the ability to relive one of my favorite memories, but now I won’t be able to enjoy those scrumptious breakfast delights much either, if at all.

Why?

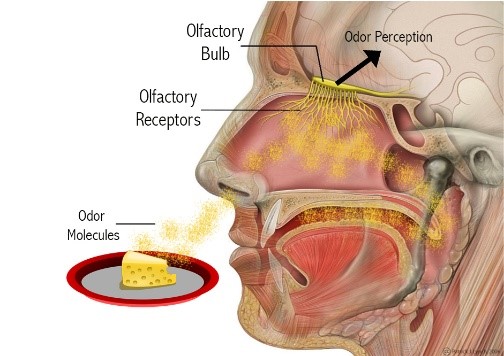

Our perception of flavor is a combination of taste and aroma. We can taste five basic qualities: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami. It is with the ascent of odors through our oral cavity (retronasal olfaction) that we may perceive flavor.1 The reason memories are often paired with unique smells is due to the way we process them. When we smell, aromas are processed by the olfactory bulb, which projects to the limbic system, particularly the hippocampus and amygdala, which are associated with learning and memory.2

And you know what else is gone? I not only miss out on the anticipatory fragrances, and the delectable flavors of this breakfast meal, but after leaving the breakfast table to retreat outside, I also miss out on other smells of life. The ethereal aroma of the windy breeze, freshly cut green grass, my puppy’s fur coat, my spouse’s signature scent. Not to mention many unpleasant aromas such as spoiled food—critical signals of danger for humans since the very beginning of our existence. Those are gone too.

Losing your sense of smell mutes the vibrant world we live in, making it desolate and flavorless. When I dove into researching this topic, I did it because I was mostly intrigued. I wanted to enhance awareness and understanding of anosmia (the loss of your sense of smell), while helping others realize how lucky they were to still have their keen sense of smell and thus, their vivacious, flavorful life! Now I am mostly devastated, angry and more motivated than ever to make people aware of the clinical need for research and treatment options for anosmia.

How does someone become anosmic?

Figure 1. The most common causes of anosmia; Image Source

Losing a sensory ability sounds relatively simple. You lose your sight and you can’t see. You lose your sense of hearing and you can’t hear. You lose your sense of smell and you can’t smell. Well yes…but you also lose your ability to experience the richness of life. For this piece, I spoke to two people who lost their sense of smell after experiencing sinus and upper respiratory infections. See figure 1 for a summary on other ways smell loss can occur.

The first person I interviewed was Chris Kelly, an anosmia activist, who lost her sense of smell in July of 2012 after a viral infection of her upper airways damaged her olfactory epithelium.

The second person I interviewed was Leah Holzel, Creative Culinary Director of Yura, freelance food editor and journalist, who lost her sense on September 12th, 2016. Leah’s food-centered profession involved smell and flavor perception which was now inaccessible to her.

“Food is a matter of civilization, social communion, and pleasure. For me, personally, food is all this, my livelihood and the great romance of my life.” – Leah Holzel

Leah Holzel further describes her loss:

People will try to define it [smell loss] as a quality of life issue, but that’s the understatement of the century. It’s not the quality of life, it is life. We scrutinize our place in the world [through smell]. Smell is a form of communication with the outside world-a way we place ourselves in time and space. If you cannot experience a breeze—it has no scent– you can’t realize the trees, the soil, –you’re losing profound communication sources of the world. You can no longer place yourself in the world.

Both women independently consulted ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists, but the doctor visits left each patient without much hope of recovery, as smell loss is much less understood than other disabilities.

The Monell Chemical Senses Center, a research institute located in Philadelphia, PA offers resources for smell loss patients. This center is the world’s only independent, non-profit scientific institute dedicated to interdisciplinary basic research on the senses of taste and smell. Additionally Professor Thomas Hummel’s work has researched therapy methods for smell loss patients. Professor Hummel is a researcher at the Smell and Taste clinic within the department of Otorhinolaryngology at the Technical University of Dresden in Germany.

Figure 2. Did you know? Facts and figures of anosmia; Image Source

Smell dysfunctions beyond lack of smell

Smell loss can be severe (anosmia) or partial (hyposmia). Recovering can sometimes include another smell dysfunction called, parosmia. Parosmia is a related medical condition in which a person can experience distortions of smell that are typically unpleasant. Something as simple as men’s aftershave can smell like pure excrement for someone experiencing a parosmic episode. The off-putting smells can often be described as ‘chemical, burnt or foul.’ The aroma of burning metal can take the place of something completely unrelated, and in such a strong way that it can carry harrowing effects on quality of life just like anosmia can. Chris claimed she did experience episodes of parosmia but has since recovered from them.

Flavorless food is a crisis already—food is fundamental to survival, but smell loss extends beyond discriminating flavor. The olfactory bulb present in mammals further evolved in humans due to important information gained from smelling. Scientists have suggested that larger olfactory bulbs (unique to modern humans) may have contributed to the evolution of our learning and socialization.3

Upon losing the ability to recognize scents, Chris said she felt “feelings of isolation, a desperation that came with thinking my life would never be the same, that I would be stuck in a flavorless, emotionless purgatory for the rest of my life.”

Leah describes her feelings about smell loss affecting more than just flavor: “Imagine you’re lying in bed with the lights out, next your partner. There is this feeling that you don’t “know” there is someone next to you. You don’t “know” the comfort, the bonding, of the relationship to this person existing next to you. There are some primitive primal things we sense unconsciously, that we are completely cut off from.

What can anosmics do?

Smell training was introduced by Professor Thomas Hummel in an article published in 20094. He found patients who smell trained fared better than patients who did not. Sense of smell was tested in the training and control groups before and after the training period. While non-trainers experienced mild improvement over time, those who practiced smell training showed improvement over the other group. This work was the first to give smell loss patients hope, and has begun to be utilized as a self-treatment by some patients with smell loss.

Smell-training consists of regular, focused and deliberate, active smelling (at least twice-daily). This is often with single-scent essential oils (Hummel’s method used rose, lemon, clove and eucalyptus) while measuring threshold level of detection and level of distortion. Undertaking a smell training practice to improve the sense of smell takes a commitment of months. The training does not cure smell dysfunction and by no means does it restore the smells of the exuberant world we live in. But from practicing daily Chris feels that smell training has given her a functional sense of smell now, of which she is thankful even if it differs from her sense before.

Neural plasticity may be a reason for efficacy associated with smell training5. It is possible that new connections (or neural pathways) in the brain formed by learning to smell again can be reinforced by practicing, strengthening these connections for better recall. In other words, smell loss patients may be able improve their sense of smell, but definitive treatments are still undefined. It is also important to note that smell training may not be for everyone—for example if a person was born anosmic, it is unlikely they would recover their sense of smell.

Conclusion

The most frustrating part about my interviews with Chris and Leah were not how difficult it was to fathom the loss of my favorite smells coupled with dimmed emotional awareness or even the idea of not having a true sense of self. It was that I could not solve the problem. I’ve spent my graduate studies revolving around olfaction but nothing in accordance with olfactory disorders and treatment options. Perhaps the most important part of this piece is to awaken your awareness for –yes, the smells around you—and yes, to appreciate them immensely—but also to promote an opportunity to help spread awareness (tell your friends!) and support Monell’s research initiative to learn more about smell loss so this doesn’t have to affect peoples’ lives so deeply.

It felt like the death of poignancy. Imagine the feeling you have just as you are dissolving into tears, whether happy or sad, and then imagine that impulse disappearing. My personality changed. -Chris Kelly

More reading:

http://www.monell.org/anosmiahope/#skills

https://www.anosmiaawareness.org/

https://www.monell.org/images/uploads/Monell_smell_primer.pdf

http://blog.monell.org/12/21/researching-smell-from-someone-who-cant/

https://www.monell.org/faculty/sense/smell_olfaction

http://parosmiadiaries.blogspot.com/2015/03/a-parosmic-at-anosmotheque.html

http://www.smelltraining.co.uk/

You can find better descriptions of parosmic experiences written by a fragrance writer (the irony is not lost to her), Louise Woollam on her blog The Parosmia Diaries.

References

- Masaoka, Y., Satoh, H., Akai, L., & Homma, I. (2010). Expiration: The moment we experience retronasal olfaction in flavor. Neuroscience Letters, 473(2), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.024

- Herz, R. S., Eliassen, J., Beland, S., & Souza, T. (2004). Neuroimaging evidence for the emotional potency of odor-evoked memory. Neuropsychologia. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.08.009

- Bastir, M., Rosas, A., Gunz, P., Peña-Melian, A., Manzi, G., Harvati, K., … Hublin, J. J. (2011). Evolution of the base of the brain in highly encephalized human species. Nature Communications, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1593

- Hummel, T., Reden, K. R. J., Hähner, A., Weidenbecher, M., & Hüttenbrink, K. B. (2009). Effects of olfactory Training in patients with olfactory loss. Laryngoscope, 119(3), 496–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.20101

- Kollndorfer, K., Kowalczyk, K., Hoche, E., Mueller, C. A., Pollak, M., Trattnig, S., & Schöpf, V. (2014). Recovery of olfactory function induces neuroplasticity effects in patients with smell loss. Neural Plasticity, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/140419

Leave a Reply