By Mary-Ann Chen

If you’ve ever ordered a side of French fries with your burger, munched on a corn dog while roaming through a theme park, or dug your teeth into the craggly skin on a fried chicken sandwich, you’re probably familiar with the irresistible appeal of fried foods. But their golden, crispy, crunchy charm isn’t without consequences; fried foods are well known for having high calorie and fat content and, if frequently consumed, can lead to health problems like type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [4].

Fortunately, as a result of consumers’ love for fried foods and growing consciousness of the link between diet and health, one unusual device has found its place in home kitchens: the air fryer! If you haven’t used an air fryer before, there’s a good chance you’ve at least encountered it in a store or on social media. This novel kitchen appliance, first introduced in 2010 by the electronics company Philips [2], has received lots of attention for its ability to “fry” foods in a short amount of time with significantly less oil.

Photo from Philips

What Are Air Fryers, and How Do They Work?

So what exactly is an air fryer, and what’s the magic behind crispy French fries that haven’t been dunked into a vat of hot oil? There are many different styles on the market, but in general, an air fryer is a countertop electrical device with adjustable time and temperature controls and a compartment, often a removable basket, that holds the food that is being cooked. The cooking process relies on a mechanism called rapid air technology, in which a heating element within the top of the machine radiates heat downward, while a fan rapidly circulates air around the food inside to heat it evenly from all angles [6]. The air-tight, compact design of air fryers ensures that all air is contained in the chamber and actively flows around the food, promoting the intensity and efficiency of cooking [6]. This mode of heat transfer is also known as convection, in which energy is distributed through the movement of a liquid or gaseous medium.

Image from Philips

Although less common, some air fryers also utilize far infrared radiation, in which electromagnetic waves with wavelengths between 3000 nanometers and 0.1 millimeters [5] vibrate molecules within the food and generate thermal energy, which accelerates internal cooking. Meanwhile, excess fat and residues typically drain into a compartment below the food to be discarded, greatly reducing the amount of fat ultimately consumed by the user.

Air Frying Vs. Conventional Frying

Unlike traditional deep frying, air frying involves the addition of only a few tablespoons of oil to coat the food before cooking, or in many cases, does not require adding oil at all. So how can a method that requires hardly any fat produce the same outcome as one that relies on liters of fat at a time? To understand this, let’s take a look at how traditional frying works.

The traditional practice of deep frying that air frying attempts to emulate has existed for millennia, from when frying was used by the Chinese in 3000 BC to pre-cook meats before roasting, to when Ancient Egyptians fried dough in oil, as evidenced in Egyptian wall paintings. Commercial deep frying became widespread around the late-1800s to mid-1900s with the emergence of cast iron kettles, edible oil hydrogenation, and sophisticated technologies for freezing, frying, and packaging of potato products [3]. Achieving a crunchy, golden-brown crust that shatters between your teeth– the main characteristic distinguishing fried foods from those that are baked, boiled, steamed, etc.– is essentially a process of dehydration. When food is submerged into hot oil between 150-200°C, heat from the oil diffuses into the uncooked food, gradually cooking it. Meanwhile, the surface temperature of the food meets that of the oil, and moisture at the surface, often from within a batter coating, quickly reaches the boiling temperature of water and evaporates out [1]. This creates the fizzling storm of bubbles that you see and hear at the start of frying. As steam bubbles break out of the food and rise through the oil, they leave behind tiny cracks and pockets that lend a porous, crispy texture, as well as enable potential absorption of the surrounding oil. While moisture is lost, proteins denature, sugars caramelize, starches gelatinize, and the Maillard reaction takes place, browning the food and imparting complex, toasty aromas. Unlike shallow frying and stir frying, deep-frying allows heat from oil to penetrate all surfaces of a food at once, leading to even, efficient cooking and browning.

Photo by Mariana Silvestre from Pexels

So how does air frying compare? In an air fryer, the medium of convective heat transfer is air rather than liquid oil, and the hot air rapidly circulating within the chamber is responsible for removing moisture from the surface of food. However, air carries less heat per unit of volume compared to most frying oils, so it must be moved at a faster rate to achieve the same effect as deep frying [6] and reach the temperature necessary for the Maillard reaction to occur, 140-165°C.

While air fryers have swept the home cooking world off its feet, like many skeptics, you may still wonder, how is this glamorized gadget any different from a convection oven? Convection ovens also rely on the circulation of hot air to cook food more quickly and evenly, but compared to air fryers, their larger size means that hot air must travel throughout a larger space and heat is less efficiently concentrated around food. Although convection ovens can accommodate more food at once, air fryers suit more uses and are generally more efficient, consuming significantly less energy and requiring up to 50% shorter cooking times and up to 75% shorter preheating times [6].

What Makes Air Fryers So Popular?

There’s no arguing that air fryers have captured the interest of health-conscious, convenience-oriented consumers around the world. Cookbooks starring the air fryer demonstrate its versatility with recipes for everything from cheesecake to homemade mini pizzas. Videos of foodies testing the limits of this curious appliance generate hundreds of thousands of views on social media platforms like Tik Tok. Air fryers are loved not just for their ability to prepare crispy fried foods with less fat and fewer calories, but also for the ease of cooking a wide range of meals with one piece of equipment. They create less mess and waste compared to deep frying and are an option for reheating food without the sogginess caused by a microwave. While no one knows if it’s just a fleeting fad, or if this unique multipurpose invention is here to stay, we can all appreciate its modern take on an age-old cooking technique.

References

[1] Farkas, B. E., et al. “Modeling Heat and Mass Transfer in Immersion Frying. I, Model Development.” Journal of Food Engineering, vol. 29, no. 2, Aug. 1996, pp. 212–216., doi:10.1016/0260-8774(95)00072-0.

[2] FnH. “A Short History Of The Air Fryer.” Food N Health, 25 July 2018, foodnhealth.org/a-short-history-of-the-air-fryer/.

[3] Stier, Richard F. “Frying as a Science – An Introduction.” European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, vol. 106, no. 11, 2004, pp. 715–716., doi:10.1002/ejlt.200401065.

[4] Sun, Yangbo, et al. “Association of Fried Food Consumption with All Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality: Prospective Cohort Study.” BMJ, 2019, doi:10.1136/bmj.k5420.

[5] Vatansever, Fatma, and Michael R. Hamblin. “Far Infrared Radiation (FIR): Its Biological Effects and Medical Applications.” Photonics & Lasers in Medicine, vol. 1, no. 4, 1 Nov. 2012, doi:10.1515/plm-2012-0034.

[6] “What Is Rapid Air Technology?” APDS, APDS, 10 June 2016, apds.nl/development-en/what-is-rapid-air-technology/.

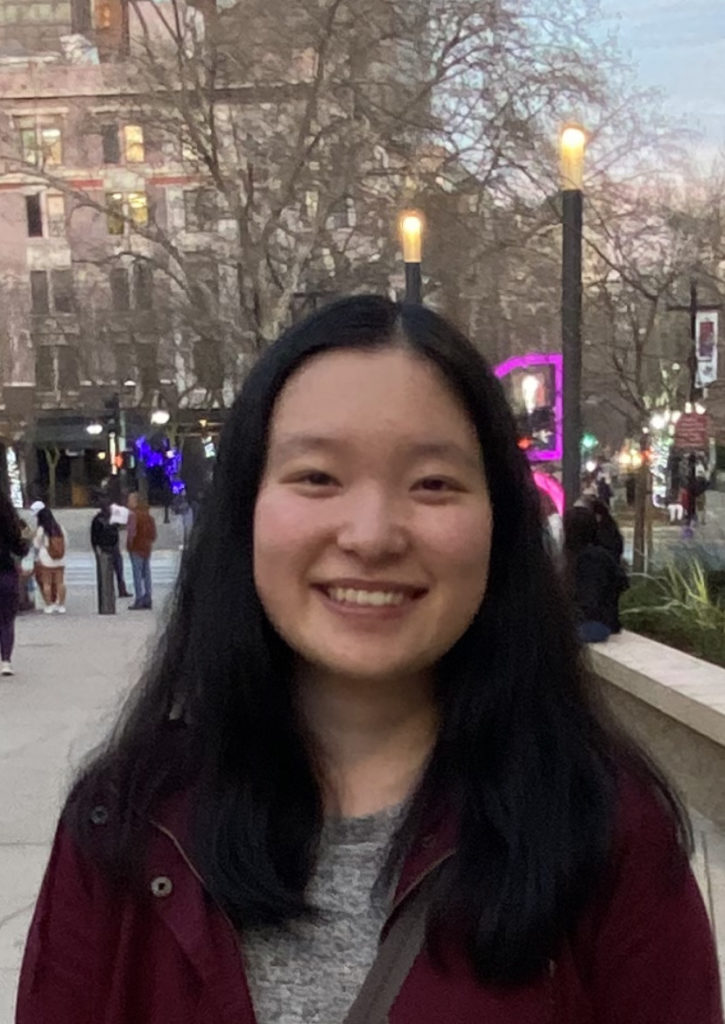

Mary-Ann Chen | Linkedin

Guest SMF Blog Writer

Mary-Ann is from Irvine, CA and is currently pursuing her B.S. in Food Science at UC Davis. She loves learning about the chemistry behind food and trying out cool ingredient combinations and hopes to find a career in developing healthy, sustainable food products (or possibly science education). In her free time, she enjoys looking for new music to listen to, reading cookbooks, playing badminton with her family, and baking different flavors of granola.

Great article from Ms. Chen, which explains the science of the air fryer! 1 thing that I learned as well from my Christmas gift air fryer is that the food aromas are different from an air fryer. The air fryer gives off a plastic smell from its heat-resistant plastic, and subsequently is mixed in with the aroma of the food as it is being cooked. For me, that is a negative factor. I’ve been cooking for over 50 years and those various aromas makes cooking more pleasant. However, the air fryer does make delicious non-greasy food. I will admit to that 🙂 which is an excellent and healthier method of cooking. Thank you!