BY: NICOLE ARNOLD

On February 12, 2018, the 9th edition of the Food Code was released as the 2017 FDA Model Food Code and, like Kim Kardashian, it nearly broke the Internet! Just kidding. Not sure many people even knew about the “breaking news,” let alone cared that it happened. BUT for those of us that love food policy, it was an exciting day. Seeing changes in the code that our friends and colleagues had initiated in the past, made us giddy. One such change was made regarding reduced oxygen packaged (ROP) frozen fish; if you’ve ever seen the “remove from packaging” statement on ROP fish (for example, the frozen fish that are vacuumed packaged individually), then you may be aware that consumers are warned to remove the frozen fish from the ROP-ed environment before thawing to reduce the risk of food safety implications like spores developing into vegetative cells (5). At the 2016 Conference for Food Protection meeting, a colleague requested that “a letter be sent to the FDA requesting the 2013 Food Code be amended to require reduced oxygen packaging (ROP) fish packaged at retail food establishments be accompanied by a label indicating ROP fish is to be kept frozen until further use and removed from packaging for thawing and that retail food establishments be required to remove ROP fish from packaging before thawing” (6). This is now reflected in Chapter 3 of the 2017 Food Code: “Amended paragraph 3-502.12(C) to add in additional exception criteria for fish that is reduced oxygen packaged at retail to bear a label indicating that it is to be kept frozen until time of use” (3).

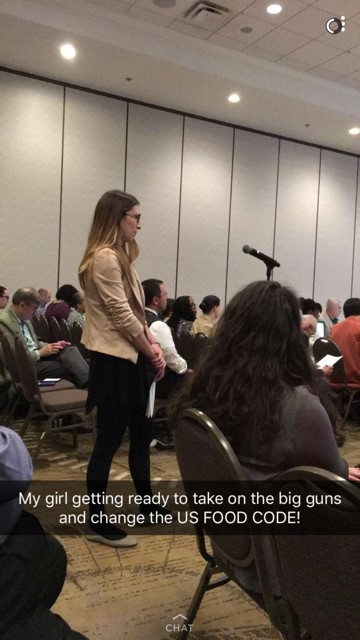

Celebrating issues being passed!

Although most food scientists are familiar with the term “Food Code”, there are few individuals that understand its inner workings: how it is updated, amended, and ultimately put into practice. The Food Code is a document that represents the FDA’s “best advice for a uniform system of provisions that address the safety and protection of food offered at retail and in food service” (1). It “assists food control jurisdictions at all levels of government by providing them with a scientifically sound technical and legal basis for regulating the retail and food service segment of the industry (restaurants and grocery stores and institutions such as nursing homes)” (2). Updated every four years, the “Model” Food Code represents the document’s most current rendition; in this case, 2017 Food Code. Individual states are able to adopt different versions of the code in order to create their specific state’s food laws. As such, this leaves some states using more updated (food) standards than others, while other states may continue to utilize outdated versions of the code for food regulation.

The most recent 2017 version consists of changes such as adding the term “intact beef”(whole muscle, intact beef defined as “whole muscle beef that is not injected, mechanically tenderized, reconstructed, or scored and marinated, from which beef steaks may be cut;” revising the term “vending machine” to be more inclusive of the diverse means of payment available; further characterizing who the Person in Charge (PIC) is (i.e. shall be the Certified Food Protection Manager); and many other various details (3). All in all, the 2017 Food Code is a fairly extensive document; 226 pages to be exact, not including the many lengthy annexes. Despite its length, the Food Code’s importance to public health remains, as it sets the standards for safe food practices across the United States.

So how does the Food Code connect to food science? Typically, Food Scientists conduct research with the intention of creating eventual impacts and/or long-term indirect effects in the food system. Research outputs are often in the form of publications in scientific journals. While we should still continue to use this type of output, there are also other meaningful ways of reaching desired research outcomes, such as using research to inform changes in food policy – go brush up on your Logic Model knowledge!

The Conference for Food Protection (CFP) is a non-profit organization that assists with the updates to the Food Code. It was created to instill a formal process where members who represent the various sectors related to food (industry, regulatory, academia, consumer-affiliated groups) can come together to deliberate the development and/or modification of food safety guidance (4).

Two years ago, I attended my first Biennial Conference for Food Protection in Boise, Idaho. Prior, I had gotten word that a previous student within my lab group was going to accompany our principal investigator (PI) to the meeting. This student was attempting to utilize her research regarding risk communication of undercooked meat at restaurants by submitting “issues” about consumer advisory warnings in restaurants to initiate changes within the Food Code. As I find food policy to be fascinating, and sometimes quite mysterious at that, I boldly asked my PI if he would take me with them. He obliged, but with the intention that I would submit issues related to my research for the conference to be held in the following two years.

I’m honestly not sure if there was another student present a the 2016 meeting, not to mention there were only a handful (at most) of individuals that fell into the academia sector, the majority derived from industry and regulatory-affiliated groups. There were three separate rooms representing the three councils that deliberated the issues using Parliamentary Procedure (Council I, II and III). I quickly picked up on the fact that if you were an issue submitter, it was in your best interest to know both the process and the people around you. I watched as “no action” (the equivalent of the issue not passing) was taken in regards to my former labmate’s issue in Council I and we responded by grabbing a beer to ease the impending pain of years worth of research being swallowed up in a matter of minutes. I was reminded by my PI that even when issues are not accepted, they still bring attention to topics that need to be addressed and often begin an important conversation.

At the time, two years seemed like an extensive amount of time (ha!); but, before I knew it, it was already time to submit issues for the Conference. This process is somewhat similar to submitting an an abstract to a professional conference. The CFP issue form requires submitters to: 1) state the issue you would like the Council to consider, 2) discuss public health significance, 3) contribute a recommended solution, and 4) provide supporting documents.

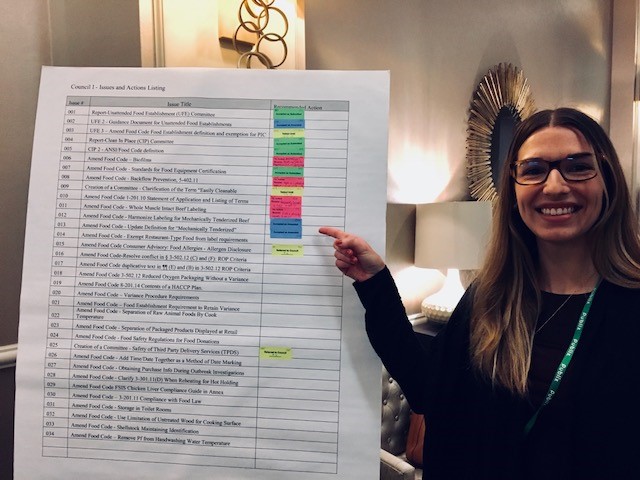

One of my issues on the screen (being amended)

My Master’s thesis embodied risk communication and food safety education themes, with some of the research having to do with mechanically tenderized beef (MTB). Although there are variations in how individuals define this term (hence some of the problems that arise), mechanically tenderized beef represents beef that has been pierced with needles, blades, or other instruments to break up muscle fibers to create a more tender product. These processes may result in a higher risk product than intact beef due to potential pathogen internalization. Therefore, tenderized products require a higher cooking temperature than those that remain intact. At the start of my Masters, MTB products were not required to be labeled as such; however, in May 2015 it was announced that MTB products would be labeled in order for consumers to be able to distinguish them from other types of beef. I view the new requirements as a step in the right direction for food safety related to MTB products, but like many changes in regulations, it comes with its own set of challenges. There is still some confusion as to what classifies a beef product as mechanically tenderized or not; the new requirements are not explicitly stated in the FDA Food Code, which may be helpful for regulators and small producers. It is important to remember that not everyone that must abide by the Food Code is a food scientist themselves, and thus the document must be clear for all parties involved; a real life application to communicating science effectively. When submitting my own issues related to MTB products (Harmonize Labeling for Mechanically Tenderized Beef and Update Definition for “Mechanically Tenderized”), I quickly recognized that while pointing out a problem with the Food Code is easy, suggesting a solution is a bit more challenging.

Once submitted, an issue editor assists with any general errors and/or recommendations that might make the language more fitting for the Food Code (i.e. verbiage, terms used, numerical adjustments, etc.) before it is then placed into a Council based upon the nature of the topic: Laws and Regulations; Administration, Education and Certification; and Science and Technology. To my dismay, both of my issues were placed in Council I, the same Council in which I had watched things go awry for my labmate two years prior.

This year, the CFP meeting was held in Richmond, Virginia; just a few hours away from the Virginia Tech campus that I currently call home. Student registration fees were put into effect for the first time (please don’t ask me how much the non-student 2016 fees were – yikes!), which I felt was progressive in itself. Although there were only a few students present, I was not alone this time. With the encouragement of my friends, colleagues, and mentors present, I was able to successfully plead my case to the Council and both issues were accepted as amended. It was agreed that the discrepancies between the Food Code and the FSIS labeling rule for mechanically tenderized beef were a larger issue than what could be solved in the little time designated to deliberating issues at CFP. It was recommended that FDA and FSIS work together to address the larger issue at hand in order to facilitate harmonization between regulatory groups and documents.

Driving into downtown Richmond, VA

Richmond, VA

It may be at least another four years until we see these changes in the code, let alone to have states adopt the newest versions of the code, however, we did accomplish something! It is rewarding to see that research I performed during my graduate work will actually have a public impact (patience is key).

It passed (as amended) YAY

Leave a Reply