By: Amelia Chen

I was in second or third grade when I had my first encounter with an edible insect. It was a chocolate covered cricket, the gift I happened to choose from our class’s Secret Santa pile. I was not pleased. It freaked me out. It still kind of freaks me out. It got swallowed up in the mess of my childhood home, and I never got a chance to find someone to pay me $20 to eat it. But as my world of food expands with my bold and proud declaration that I would try everything at least once, the idea of insects as a future food source is becoming less and less cringeworthy.

Chocolate-y cricket… Ok they don’t tend to look this cartoonish. Source – peppersteakandpolyester.com

Insects, after all, are arthropods. And the most luxurious arthropod of all – lobster – used to be regarded as repulsive and fed to pigs and prisoners. Times are changing. The population is growing. And creepy crawlies (in the context of food) aren’t just neon colored, sour gummies anymore. For the developed world. In many developing countries, entomophagy, or the consumption of insects as well as arachnids and myriapods, is already a historical and popular practice.

Source – newglobalcitizen.com

Today, you can find an abundance of fried, grilled, roasted, and even raw critters in Asian, African, and South American countries. There’s a whole market dedicated to them in Thailand, termites are a means of survival in Ghana, and minty ants are celebrated in Brazil. And why not? They’re everywhere, and on paper, these exoskeletal animals are tiny nutrient treasure troves. Protein – check. Unsaturated fats – check. Vitamins and minerals – check. Insects are comparable to seafood, beef, and eggs for grams protein per 100 grams, but where most critters win out is in the vitamin and mineral content. Crickets, for example, contain 12.9 grams of protein for every 100 grams, as well as a lot of iron, calcium, and vitamin B12.

Source – Macleans

Developed countries are taking notice too because several companies are popping up with their own bug products. Six Foods makes cricket flour chips, Green Kow offers sweet and salty mealworm spreads, and Ento is gearing up to launch their own delicious products while hosting tastings in the UK. And I’ve tried Chapul cricket bars, which were pretty tasty, especially because the cricket part was seamlessly blended in. IFTSA is also staying on top of the trend with the Developing Solutions for Developing Countries theme of last summer, which centered around insect protein. Our own team at UW-Madison actually took second at the competition with their Nu Stew product – a groundnut stew with spent silkworm pupae for Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya. This competition also highlights the economic and environmental feasibility of entomophagy. Silkworm pupae are the byproduct of the growing silk industry. Once the silk fibers from the cocoon are spun, the pupae are usually given to animal feed, but they are rich in protein, unsaturated fats, fiber, calcium, and iron, making them an excellent source of nutrients for people, as well.

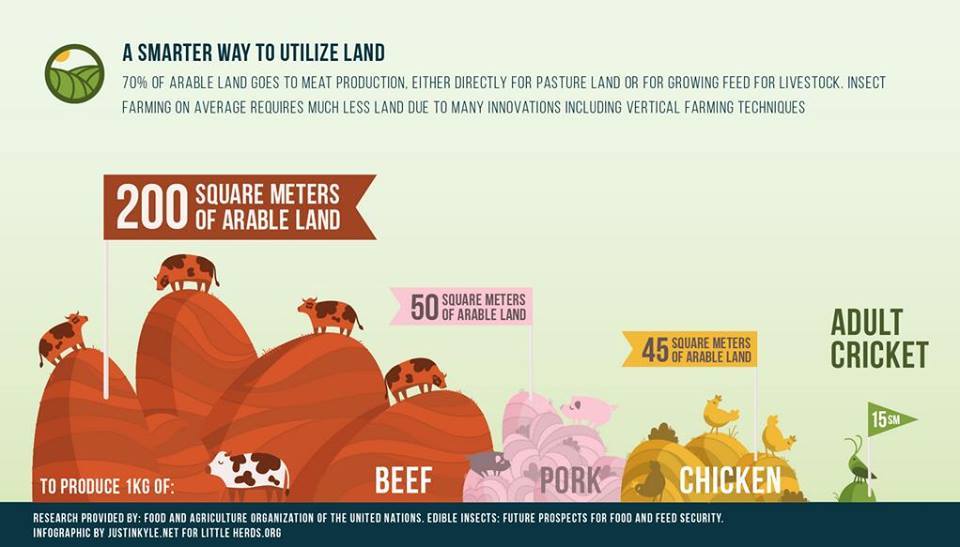

Infographic on the land utilization of protein sources. Source – littleherbs.org

Insects require much less food, water, and land to raise compared to livestock. They’re tiny; makes sense. But insects are also incredibly efficient at converting feed into edible meat. For comparison, a pound of beef requires 25 pounds of feed, while a pound of crickets requires only one to two pounds of feed. These environmentally friendly critters also emit much less greenhouse gases than cattle.

Insect stir fry. Source – livescience.com

But just in case you were about to step out into your backyard in search of lunch, you should know that not all insects are safe to eat. Excluding poisonous species, there are still a number of risks to consider. In many of the places where entomophagy is common, the insects are harvested from the wild, which makes it impossible to determine what toxins or pesticides they have been exposed to. They may also carry harmful bacteria or compounds that can lead to illness, so it is important to know where you are sourcing your insects before tossing them into your stir fry.

While the case for insects as our future food source is tempting, it should not be overlooked that rearing insects as a food source requires the same considerations as rearing livestock if the ultimate goal is environmental sustainability. Insects require a warm environment to grow, and researchers at UC-Davis showed that crickets had a higher protein conversion rate when raised on poultry feed. Ultimately, bugs “will only be a real part of the solution if we are careful and thoughtful about how we integrate them into the food system.”

So if anyone is looking for ideas to host a new kind of dinner party, I’ve got a pre fixe menu for you:

Apps

Beer battered platter of grasshopper, crickets, and locusts with trio of dipping sauces

(hummus, garlic yogurt sauce, tomato chutney). Probably the first things you think of prepared in the first way you think of when talk of insect edibles comes up

Witchetty grubs bruschetta. Supposedly nutty with egg-like insides wrapped in crispy

skin, these grubs are a common in Australia (image: http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/02706/witchetty-grub-suz_2706196k.jpg)

Entre

Deep fried taratula po’boy. Popular in Cambodia, these guys are said to taste like soft

shell crab, so season with white pepper, lime, and salt and toss them in a

sandwich with lettuce, tomato, and creole sauce (image: https://encrypted-tbn1.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcSpYhfyhG6wq3B2NUyJZux-889D7J4GEF-pItPGm7pP9OJYBMG-pQ)

Mealworm tacos with onion, cilantro, avocado, queso fresco, and salsa verde. Beef

tongue is out, mealworms are in (image: http://www.viralsoma.com/uploads/7/0/4/9/7049688/4585713.jpg?705)

Dessert

Chocolate souffle. Made with cricket flour, of course.

References

Anthes, E. “Could insects be the wonder food of the future?” 14 October 2014. BBC.com. <http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20141014-time-to-put-bugs-on-the-menu> 19 October 2015.

Bryant, C.W. “How Entomophagy Works.” 15 April 2008. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://people.howstuffworks.com/entomophagy.htm> 19 October 2015.

Holland, J. “U.N. Urges Eating Insects; 8 Popular Bugs to Try.” 14 May 2013. News.NationalGeographic.com. <http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/13/130514-edible-insects-entomophagy-science-food-bugs-beetles/> 19 October 2015.

van Huis, A. et al. “Edible Insects: future prospects for food and feed security.” 2013. <http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3253e/i3253e.pdf> 19 October 2015.

Weiner, M.B. “Countries that Eat Bugs” 11 April 2014. <http://travel.usnews.com/features/Countries_That_Eat_Bugs/> 19 October 2015.

“What is Entomophagy?” 2009. InsectsAreFood.com <http://www.insectsarefood.com/what_is_entomophagy.html> 19 October 2015.

Oaklander, M. “Eating Insects isn’t as Eco-friendly as People Say.” 20 April 2015. Time.com. <http://time.com/3824917/crickets-sustainable-protein/> 19 October 2015.

Other Images

http://www.macleans.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/MacBlog_Insects_03.jpg

Have you checked out other dessert options… http://hotlix.com/candy/

C:

!!!