By: Ty Wagoner

Move over, kale. See you later, açai. Turmeric is the new super food in town.

In classic “old is new” fashion, food manufacturers (and the growing nutraceutical market) are turning to the foods of yesteryear as the next big thing. Much like its rhizome relative, ginger, turmeric has been used in foods, cosmetics and medicine for nearly 4000 years. Yet with the spotlight surrounding its recent health benefits, turmeric is now appearing in exciting new places.

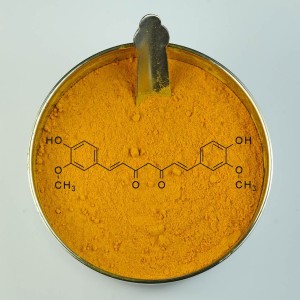

Turmeric is a rhizome (think “root”) derived from the medicinal plant Curcuma longa. Over 100 unique volatile components have been isolated from turmeric, but the primary polyphenolic component is a curcuminoid appropriately named curcumin (no relation to the spice, cumin, other than both being delicious). Curcumin – with its structural array of conjugated double bonds – is responsible for the color of turmeric and many of the published health benefits.

Structure of Turmeric courtesy of scilogs.com

The earliest use of turmeric was as a dye for clothes, paper and foods. It produced a brilliant yellow hue, earning it the moniker “Indian saffron” and making it an inexpensive ersatz version of saffron. Today, turmeric is widely used as a natural yellow colorant (E100) with a hue similar to that of annatto (E160b). Both are commonly used in the food industry to color yogurts, mustards, cheeses, butter and dry mixes.

Cheese courtesy of automationheroes.com

Super original meme created at imgflip.com

The use of turmeric as a colorant in foods is widely established. However, the shirt-staining power of turmeric (yes, I speak from experience) extends beyond the kitchen into the research lab. Recent studies indicate that curcumin can be used as a non-toxic stain for proteomics and electrophoresis. Kurien et al. (2014) reported that in addition to being inexpensive, heat-solubilized curcumin has a similar sensitivity to common stains such as Coomassie brilliant blue. Unlike traditional stains, however, curcumin can be disposed of directly onto a bowl of rice (okay, maybe just down the sink). Researchers have also developed a food-grade method for the colorimetric detection of volatile amines associated with seafood spoilage. Curcumin can be adsorbed onto cellulose membrane within a packaging material, and the accumulation of volatile amines modifies the pH of the headspace, changing the curcumin sensor color from yellow to reddish-orange to indicate spoilage.

But turmeric is more than just a pretty color. In a culinary context, turmeric is a staple ingredient in a number of cuisines, where it contributes a mild flavor, slight bitterness, and a ginger-like floral redolence. India produces most of the global supply, so its fits that turmeric would be omnipresent in Indian recipes (it is a component of curry powder, for example). It is also a common ingredient in Southeast Asian, Middle Eastern, and Ethiopian cuisines.

Its recent surge in popularity is likely due to potential health effects. Over the past 20 years, thousands of research studies have linked turmeric with potent anti-oxidative, anti-viral, anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, and cardioprotective effects (at least in vitro and in animal models). Thus, one of the biggest growth areas is in the nutraceuticals market segment, with turmeric permeating into a variety of product categories including teas, snacks, and ready-to-drink smoothies. A quick Google search reveals that even hand lotions and shampoos are proudly sporting turmeric on the front label. Many studies are also looking into the application of curcumin with current chemotherapeutics and antimalarial drugs in animal studies and have shown positive results. Expect to see turmeric popping up in the grocery aisle (and beyond) a lot more over the coming years. Oh, and in case you’re wondering, both pronunciations (TOO-merik and TUR-merik) are correct.

Its recent surge in popularity is likely due to potential health effects. Over the past 20 years, thousands of research studies have linked turmeric with potent anti-oxidative, anti-viral, anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, and cardioprotective effects (at least in vitro and in animal models). Thus, one of the biggest growth areas is in the nutraceuticals market segment, with turmeric permeating into a variety of product categories including teas, snacks, and ready-to-drink smoothies. A quick Google search reveals that even hand lotions and shampoos are proudly sporting turmeric on the front label. Many studies are also looking into the application of curcumin with current chemotherapeutics and antimalarial drugs in animal studies and have shown positive results. Expect to see turmeric popping up in the grocery aisle (and beyond) a lot more over the coming years. Oh, and in case you’re wondering, both pronunciations (TOO-merik and TUR-merik) are correct.

Leave a Reply