By: Amanda Sia, Abbie Sommer and Mackenzie Hannum

Featured Image by Pickwriters

“The time for food is now.” – Maria Velissariou

Food science is a major and a career that spans across many disciplines. Some people study chemistry, microbiology, statistics, engineering – the list is endless! And as food scientists, we learn a little bit of all of it.

In our interview with Maria Velissariou (Read Part 1 of the interview HERE), the Chief Scientific Officer of the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), we learned that food science can be even more than those core disciplines. By fostering collaboration and integrating knowledge of how food gets to consumers and what happens after the factories ship it out, we can meet the changing and increasing demands of consumers.

The food industry, as well as the wants and needs of consumers, are evolving.

“This industry is being disrupted and we’re using innovation and disruption. What is the difference between the two? Disruption is what happens to you, whereas innovation is what you make happen.”

Many things are leading to the disruption of the food industry including consumer wants and needs and technological innovations. The food industry has to be “disrupted” in order to adapt to the changes. But who is making these changes?

“The startups and small companies innovate and disrupt. Big companies—they innovate and nowadays, they have started to embrace being disrupted. A lot of big companies actually have their own corporate venture capital entities, because what you cannot fight, you have to embrace. The individual startup is not big enough but collectively, they’re a force to be reckoned with.”

Small companies have traditionally been those that embrace disruption, whereas large companies have been more focused on innovation and creating their own trends. Nowadays, large companies are adapting to meet the force of small companies. The industry is making the changes necessary for our society, but how does academia rise to the challenge?

“The science of food has always been interdisciplinary by nature, but it needs to be more interdisciplinary.”

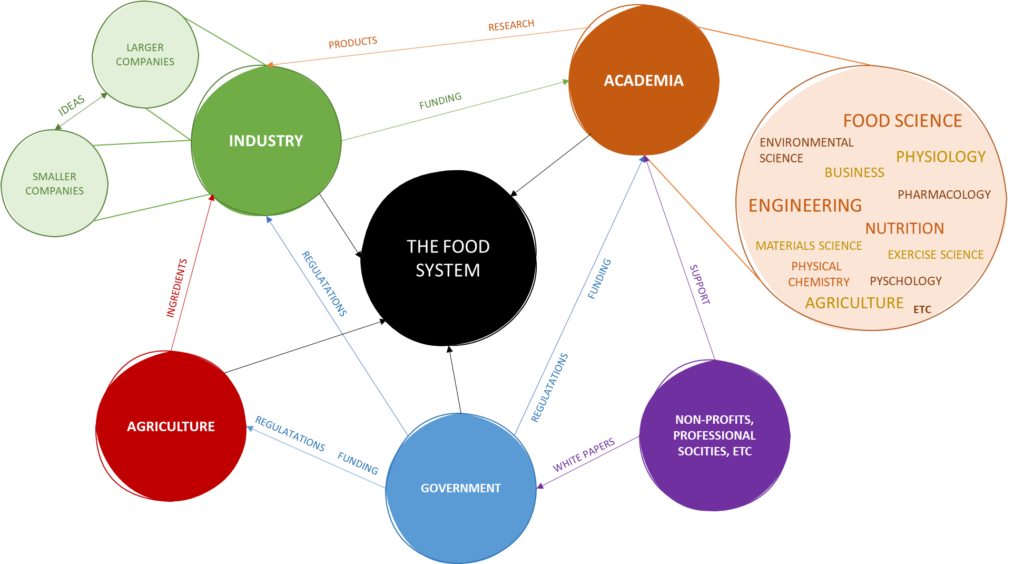

There are natural collaborations that are already happening in academia like those between food science and engineering or nutrition. However, more collaboration could exist between disciplines, across industry, government, and academia, and even amongst companies.

Figure 1: A very simple infographic of a very complicated food system

Infographic by Abbie Sommer

When asked what changes could be made to the educational curriculum of future food scientists, Maria drew upon a more holistic view of the food system:

“More familiarity with up streams and down streams of food science—more appreciation for aspects of agriculture and more appreciation for aspects of nutrition, human physiology, and environmental disposal.”

As food scientists we are intimately associated with everything that has to do with food, but only during a specific time frame across the entire food product’s life cycle, usually the development and processing part. I personally have studied food science at two large agriculture universities and have never been required to take a class related to agriculture or environmental science. While “we cannot be scholars of all”, it is important to have an understanding of the larger map of inputs and outputs and a true appreciation for the life cycle of a food item from farm to table.

Figure 2: Image by klimkin from Pixabay

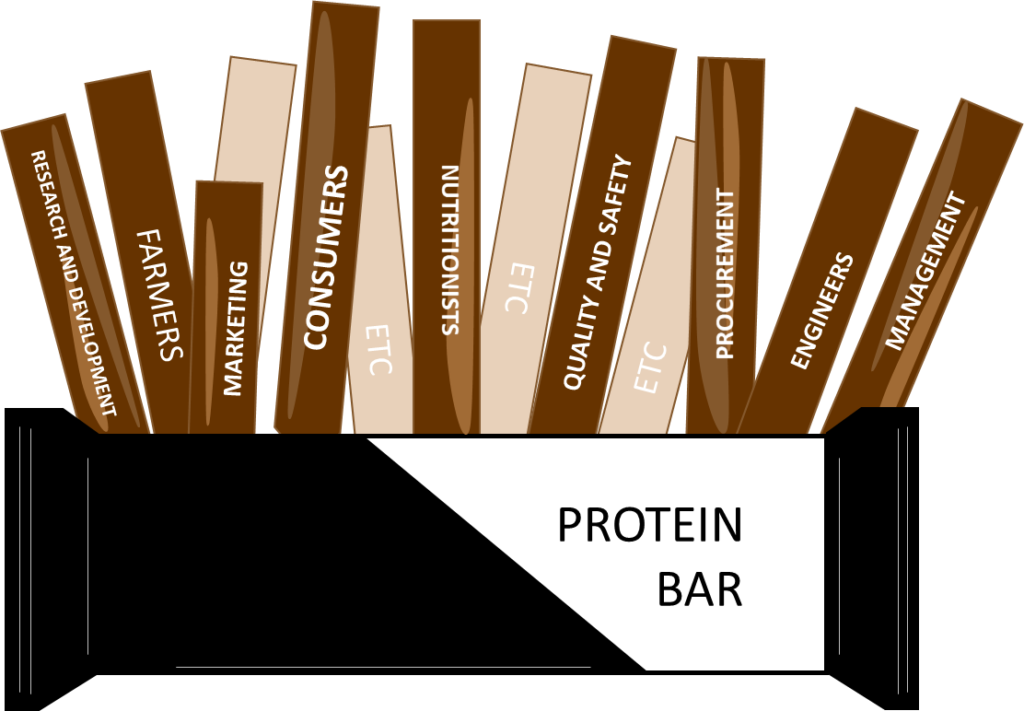

Working together helps us to understand the perspectives of different disciplines. Take a protein bar, for example. A food scientist had to develop that protein bar to meet the standards of the sports nutritionist, in order to help improve performance or enhance the recovery of an athlete.

Figure 3: Some of the stakeholders (stakes) in the food industry (protein bar)

Infographic by Abbie Sommer

A farmer can only produce the raw ingredients during a certain time frame or season. A food scientist may want to create a product that tastes good but is also shelf-stable and safe for consumption. Engineers and technicians in the plant want to make sure they can produce the product with the equipment the company already has, with ingredients that are free flowing and easy to process. Those in business or marketing want to make sure that the product has certain health claims like “high protein” or “excellent source of fiber” and that the product is cost-effective to make. The target consumer may want a product that is high in protein and low in added sugar. With the many groups involved in our food system, it is important to approach it with a holistic perspective and take into account other viewpoints.

Communication between multiple stakeholders helps us to create products that are relevant to consumers. These different stakeholders have varying goals with a product, and we can learn from these different goals to create something best suited for the consumer.

Figure 4: Image by TeroVesalainen from Pixabay

That being said, collaboration is not always easy.

“It is not always straightforward and obvious to work with people from other fields… they bring their own mindset and approaches. It is a challenging thing to do, but also very stimulating and motivating to find ways to work within those teams.”

Despite the difficulty, within academia, these collaborations are starting to happen. However, there is another challenge of a lack of funding from both government and industry, especially when trying to understand fundamental concepts. Funding from industry more often goes into product development type projects, with a quicker turnaround and return on investment.

Yet is important to understand the more fundamental knowledge that could lead to advances in the future.

“Investing in academic ecosystems will be an important driver for scientific discovery and academic excellence. The funding for the science of food is a catalyst for discussion. Right now, IFT is preparing a white paper. We’re seeing that food science is significantly underfunded compared to other sectors like pharmaceuticals or even agriculture. So, we have a gap in the whole space of basic, fundamental, and translational research. Today we are not getting enough public funding there and we do not see the right amount of public/private partnerships to build and address this void.”

Fundamental understanding of concepts like water activity later led to innovations in extending shelf-life, preventing microbial spoilage, and mitigating lipid oxidation. What are some other advances in food science that could happen if we invested more in fundamental research, especially in interdisciplinary projects?!

Figure 5: Image by congerdesign from Pixabay

We have talked about working together to address the needs of many stakeholders but with all these different groups involved, there are bound to be multiple issues that impact each differently. But what is the one issue that impacts all of us – the consumer, the food scientist, the government, the citizen? When we asked Maria, she said:

“The issue that is impacting us all is food security – making sure that we continue to have uninterrupted availability of safe, nutritious, affordable foods for all.”

Feeding the world is an issue that is growing in importance every moment. Food scientists, along with many other professionals, academics, and governmental agencies, will be the force that is working to solve this issue in the future.

“[Food science] is about developing products, it is about optimizing products, but it is also about feeding the world.”

In our conversation with Maria Velissariou, all three of us walked away inspired and excited about the career of being a food scientist. She reinforced the importance of collaboration between the many stakeholders in the food industry. We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Maria Velissariou for sharing her breadth of experience in the industry and allowing us to share our experience with the Science Meets Food readership.

Amanda Sia | Linkedin

Amanda Sia | Linkedin

Amanda graduated with her M.S. in Food Science at The Ohio State University. Her research focuses on using vibrational spectroscopy data to build predictive models for use in quality assurance settings. Amanda received her B.S. in Food Science from University of Minnesota (a shocking change of environment since she is originally from Malaysia, a very tropical country). When she is not scanning peanuts in the lab, Amanda likes to play squash, sing in the shower (sorry housemates), watch sappy Korean dramas, and play the guitar.

Abbie Sommer | Linkedin | Website

After graduating with a B.S. in Food Science from Purdue University, Abbie decided to move one state over to pursue a Masters from Ohio State. Her research is focused on soy-based functional foods for use in clinical trials. When she’s not making thousands of soft pretzels (for science, of course), you can find her training for half marathons or experimenting in the kitchen. Recently, Abbie has developed a passion for sourdough and treats her starter like a child. She also has a recipe blog (Sommer Eats) as well as an Instagram account (sommer_eats), where she posts somewhat healthy but always delicious recipes.

Mackenzie Hannum | Linkedin

Mackenzie graduated with a B.S from The Ohio State University in Food Science and couldn’t get enough of it so decided to stay at Ohio State to pursue her PhD in Food Science with the focus on sensory science. Overall her research investigates panelist engagement and ways to improve sensory methodology. Fun fact about Mackenzie is that her 5th grade science fair project explained the concept of the 5 basic tastes so in a way she has come full circle. As much as she prides herself now on being a true foodie, ready to try all things sans olives, she will admit her two all-time, indisputable favorite foods are pretzels (any kind) and plain bagels. Truly…if she was stranded on a deserted island with only one food item it would be a tough battle between the two but pretzels would win out. Hard, soft, sourdough, sticks—you name it!

Great post – very insighful.